Source: en.xfafinance.com/html/Economies/Trade/2017/320023.shtml

Source: en.xfafinance.com/html/Economies/Trade/2017/320023.shtml We will start today’s review of Australia’s Eastern rail network with a situation report:

http://reports.weforum.org/global-competitiveness-index/competitiveness-rankings/#series=EOSQrailroad

Hence Australia’s railway infrastructure is ranked by the World Economic Forum at no. 36 in the world for competitiveness, and it cites a negative trend in their survey. Besides the major western & eastern powers, Australia ranks behind states like Ukraine, Estonia, Azerbaijan, India, and we are only 2 positions ahead of Indonesia which has a fast rising trend.

Crucially, our WEF survey rail ranking is 18 places behind Canada, which is our closest economic analogue. This is despite our overall WEF cited competitiveness ranking being 22, and only 6 spots behind Canada. Our lesser rail competitiveness is a part of that difference.

We should also pay particular attention to the existing higher rail infrastructure rankings of the emerging soft and energy commodity producing exporter states in international markets, those same seeking status in the One-Belt-One-Road initiative such as Russia and Ukraine.

First trainload of Russian wheat arrives in China:

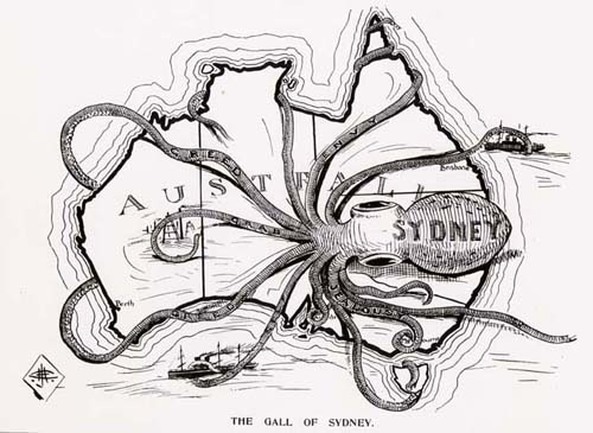

In the first half of the 20th century Australia had a rail infrastructure competitiveness lead over many of our contemporaries. We gained that lead by seeking to invest in order to facilitate an export-oriented economy, and by means of our ports competing among themselves for that same trade. We also made wise down-payments in cities, especially so in Sydney, in urban heavy weight rail corridors (as we did in other renowned first world urban infrastructure like water and sewers).

In citing the aforementioned we should not avoid confronting the “Gold Plating” cultural overhang that my father said his post-WWII generation believed they had to bear the tax responsibility for. Neither should we allow a ticket-of-leave to the accompanying economy-of-scale orthodoxy employed by monopolists in having secured the exclusive or duopoly license regimes that accessed it, and served to restrain or degrade its economic potential. We will not dwell on these elements further here, but we will mark them as noteworthy contestable subjects.

In respect of redress to the historical anti-competitive issues that affected rail freight in Australia, we must mention that the Standard Gauge network, based upon the historical NSW state gauge, has grown in the post war period. It now corresponds with the Commonwealth government owned ARTC line network that is shown in deep red on the map in part 1 of this series, plus the remainder of the NSW operating lines. The majority of these standard gauge lines are leased from the respective States. Otherwise states retain their legacy gauges.

There is also an access regime and competition supervision (more on that later). Together with the proposed additional sections that should come together to form a contiguous Melbourne-to-Brisbane rail line, which in the northern corridor will mainly will be dedicated to freight operations, there may well be the basis of a spine for a future rail freight network as conceived in many other more economically competitive countries.

In NSW there has been substantial capital investment in urban rail yards, and in dedicated freight lines in Sydney. There has, however, been little investment by way of comparison in regional rail yards (we will also be returning to that issue later).

While we are on the subject of contestable government sponsored infrastructure history, however, I will mention the two incongruous state funded infrastructure developments in the post war period. The first was the Snowy Mountain Scheme which is well known for its hydro electricity component but less so for its boost to the Murrumbidgee Irrigation area. Twenty years later were the NSW black coal-fired power station developments delivered during the 1980s. In an era when infrastructure project funding typically reached only 0.40c in the required dollar, these were a return to the pre-war gold plating.

The released Fraser Government Cabinet papers to date do not confirm the view, held by some, that the raison d’être of Commonwealth support for the level of investment in electricity supply growth in the 1980s was that the Government saw East Coast intercity and regional rail electrification as an appropriate strategic response to geopolitical events surrounding the ‘70s oil crisis. Having been involved in the import and delivery to site of the major electrical control equipment for the new black-coal stations I can recall that view being held by engineers at the time.

I have also heard the above proposition firmly denied by those that claimed to have been Fraser Cabinet attendees, but my point here, in citing this controversial matter, is that strategic ends have a habit of being revisited in history. Australia has long had dwindling local oil reserves, and we do not have significant diesel or avgas fuel production capacity. It is, therefore, also strategically noteworthy that Australia’s logistical backbone is, in the absence of rail electrification, or some new technology, heavily dependent on these same refined energy sources.

From the 80's onward, however, there was political blowback led by the NSW Greiner Government in particular, and governments reverted to neglecting investing in baseload electricity generation capacity. Today we have a crisis as a result. We won't be revisiting this matter later in the series as our proposals revolve around diesel powered traction, but these abrupt investment cycles are noteworthy, and form part of the dysfunctional environment we are confronting.

Finally, we have delivered a smaller sized post today, more in line with norms for this genre. Still, however, we have yet to address specific contemporary proposals, or their reviews. We promise to make more headway on specifics next time.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed