Smaller Efficiencies

“Adding power makes you faster on the straights, subtracting weight makes you faster everywhere.” Colin Chapman - Lotus Cars

Image: Automated Straddle Carriers, www.cargotec.com

Image: Automated Straddle Carriers, www.cargotec.com 1. Less government

2. Less organised industrial labour

Today, when trains are being driven remotely, and port terminal automation is emerging, we don’t have to concentrate solely on the confrontational. Moreover, in respect of organised labour, it isn’t worth the type to cite the number of times unions have shot their members job interests in the foot. Nor is it necessary to demonstrate the propensity of governments and monopoly rights holders to ruin the underpinnings of trades passing through their controlled ports.

When we envisage a new smaller port entity our imaginings include the employ of geared ships, automated straddle carriers, and automated or remotely controlled entry & security.

We have previously commented in this blog about so-called 'leading edge' government security and intelligence developmental programs. In the interests of improved supply chain infrastructure we call upon proponents of such new schemes to put-up, or shut-up, about the supposed wider benefits of such new systems. It is time to stop simply putting more layers on a cake built by government – for government. If any new supposed end-to-end system or participant gate-keeping system has intrinsic value - it should displace the existing high-cost-low-intervention fixed regimes in place at ports.

In respect of port automation, the concept started with the now typical "go-big" capital intensive vision. This is perfectly illustrated by the early large-scale automation environments delivered in Holland. One of these terminals is showcased below:

Given the capital intensity, and the maintenance/operating complexity of a Rotterdam styled development, this vision is ill-suited for our purposes. There is, however, a more interesting concept for us. It is the one first employed by Patrick at their medium-sized container port terminal in Brisbane. Patrick terminal operations and Patrick Automation, pioneered the world's first and only free ranging robotic straddle carrier terminal in the regional port of Brisbane in late 2005 as announced below:

(www.cargotec.com/en-global/newsroom/Releases/product-releases/Pages/automated-straddle-carrier-facility-wins-terminal.aspx).

The background, from the local region's viewpoint, was that Brisbane was a smaller container port than either its Melbourne or Sydney competitors. Hence, they accepted an automation solution that lowered their cost base, which in turn allowed them to solicit business more aggressively, in pursuit of growth in their port's container handling market share on the Australian East Coast.

Patrick's focus on a single piece of automation equipment is more fulsomely described by their management here:

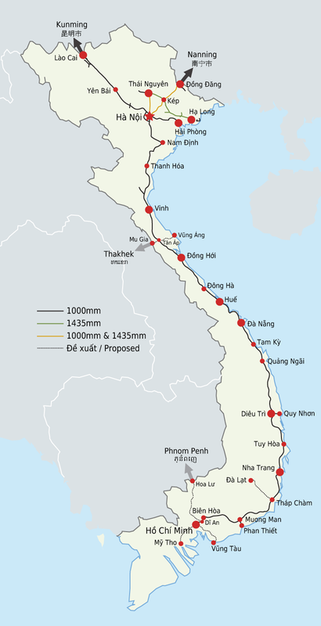

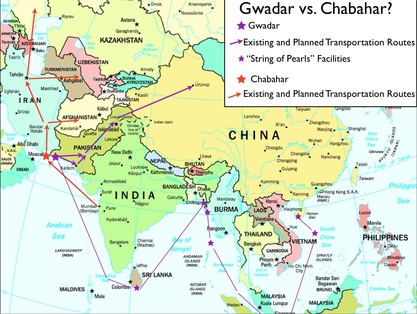

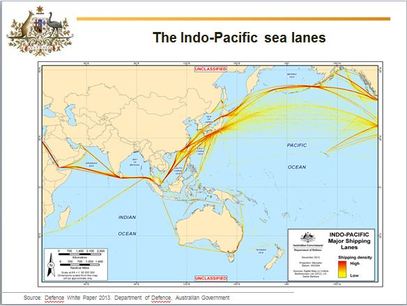

We foresee similar contests being launched by small ambitious ports globally. Such ports may seek to both lure trade away from mega-hubs, and facilitate the emergence of new trades. Despite the auto straddle based solution described above now being deployed in larger Australian ports (those that are trying to maintain their competitiveness regionally), we see the greater potential being for this style of developmental road to go the other way in terms of scale - to enable the redevelopment of smaller coastal ports - on a global basis.

The limits of this scenario, in terms of a minimalist feasible scale, are yet to be explored in the competitive sense. Lesser defrayed costs achieved through economy-of-scale in the areas of port maintenance, craneage, and the unit costs of larger deep water vessels employed in existing trades must be acknowledged. So too, however, is the velocity of adaptation available for small flexible ports to take advantage of trade opportunities. There is the possibility that direct small region-to-small region trades prove more efficient than trades dependent on capital intensive & heavily government subsidised mega port hubs. The smaller region prototype ports we have described may also be replicated at forsaken city terminals in major hub ports giving them last mile delivery cost/service advantages.

In respect of hinterland / regional / or coastal transportation infrastructure, given equivalent terminal access availability & cost, why a logistician would promote the preferred employ of a truck over a train at anything over a single day’s transit is beyond us. Similarly, why you would employ a train versus a ship for points to/from near-coastal origins and destinations with a transit above 3-4 days beats us too.

Yet, as the truck is rationally seen as more accessible and flexible than the train, and the train having a similar advantage over the ship, we regularly see the wrong tool employed for the right reason. Inefficient infrastructure is plainly negating the aforementioned “given”, but the there is more to it in terms of causation. One noteworthy point to make before we proceed further is the earlier discussion in respect of the contest for a mega hub's inland infrastructure, and rail in particular. It is the cost!

So we return to the questioning. How often have we heard road and rail infrastructure development proposals dependent on public funding (or guarantees) were flogged in the political domain by merchant bankers at contrived cost estimates that proved to be 20c in the dollar of the eventual outcome cost?

Could we imagine the current crop of ascendant lobbyists & cash-for-comment "experts" proposing a series of upgraded small / low-cost international ports? It is also hard to imagine the current cohort of executive cadres exploring proposals for public funded projects that would reduce aggregate inland transportation infrastructure spending. It appears that contemporary infrastructure development proposals that are wrapped in rhetoric about improving speed-to-market, & the lowering of supply chain costs, must always be about the highest public cost option, and the boondoggle real estate development corridor.

At this point we should post a reminder of matters covered earlier in respect of regulatory and monopolistic opportunism that have played there part through political/state channels. Primarily we are talking about state's publicly funded development measures that seek to entrench the primacy of existing hub ports and prevent the rise of regional competitors. The conduct of ports protecting their patch is a global phenomenon, but it is usually facilitated by an untested any-infrastructure-is-good-infrastructure argument. We see this as folly. Such an argument can be plaintively demonstrated to have had a degenerative systemic effect in the logistical, economic, and trade facilitation sense, if contemporary levels of trade and purchasing power polarity are acknowledged as unsustainable.

This brings us back to our speculation concerning the potential of smaller container ships, those that might effectively compete with larger hub-calling vessels. Initially, in this series, we looked at images of smaller ships with clear decks and rotors, or geared ships with substantially clear decks and sails, as shown here:

www.skysails.info/skysails-marine/.

We imagined the potential for the design of smaller cellular below-deck container ships that may employ dual-use gearing (ships cranes) in combination with wind harvesting sails, or rotor designs. We imagined such a ship, with bow thrusters, self-discharging at a series of purpose built low cost regional ports absent of cranes and facilities. Speculatively, we would envisage a new generation of the so-called "Liberty Ship". We see the possibility of principal vessel operators serving direct regional trades and the now defunct city terminals of mega-ports in these purpose-built ships.

Automated straddles, remote operation, and remotely monitored security, have the potential to lower labour costs in the above scenario. There is inimical potential to compliment this by removing the need for wharf cranes and to reduce both facility & hinterland infrastructure spending. Acknowledging the economy of scale arguments in favour of larger ports, this style of regional port should not seek to serve ship's crews ashore, nor generally provide bunkering or maintenance facilities. Resisting the pimping by regional communities for direct local economic spin-off from expanded small port activities, those directly related to operations, would be an essential strategic element.

In respect of existing feeder-vessels, those that already support mega-hubs and medium-sized spoke ports, we foresee few of the existing vessels in these trades entering the regional trades we describe. Many of these vessels are ungeared, & any such ship unable to self-discharge in our low-rent environment would compromise the minimalist infrastructure paradigm. We note too, that these same existing feeder vessel operators are presently on a hiding-to-nothing while indentured to the mega-hub and mega-ship operators in the polarised east-west trades, as evidenced here:

http://theloadstar.co.uk/feeder-line-chief-warns-deepsea-carriers-to-focus-more-on-value-rather-than-cost/

We foresaw the feasibility, in the small port environment, to implement a policy where all landed containers were straddled and loaded intermodally out of the terminal within the ship’s port-call window. Uncleared containers could be automatically retrieved from the terminal by opportunistic bonded storage operators. Although this same aspiration is shared by most existing larger port terminals, the ability to implement & supervise it, and hence mitigate security-related issues, is the greater in the small port operating environment.

And despite the barren image we project of our minimalist regional & city port facilities, we close this series by imagining the vitality of the trades, and the increased access to opportunity and jobs, that new regions being able to directly access global trading opportunities may bring.

And so we conclude this series, and thank you for your attention.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed