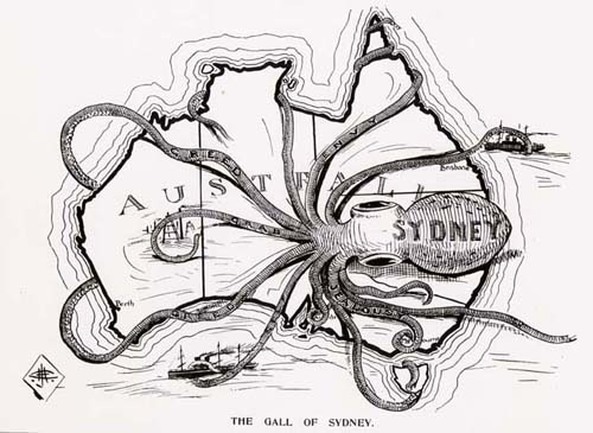

The Australian Constitution Convention as seen from Adelaide. Source: www.slsa.sa.gov.au

The Australian Constitution Convention as seen from Adelaide. Source: www.slsa.sa.gov.au We need to make more of an impression in respect of the detrimental impact of political legacies upon the relative productivity & economic capacity of the Australian nation versus contemporaries. This applies especially from the latter half of the 20th century when investment in the rail sector was curtailed.

Today we intend talking about Australian monopolies and duopolies, but to do so we must once more return to the 19th century. And yes, principally, our chain-of-events involves the issues of protectionism, state political borders, and state controlled primary hub ports. We are concentrating on the period through to the political birth of the Australian nation (the Federation of the Commonwealth), which was finally proclaimed in 1901 after 20 years of negotiation.

Starting from the 1850’s, the individual colonies that were later to become states, each shared the bright idea that they would implement different rail gauges. This was driven by trade protection interests that sought to secure goods emanating or destined for their state, to depart or arrive through their state’s ports. Likewise, produce or manufactures from interstate would become subject to a form of non-tariff barrier. The duties, taxes, and economic spin-off associated from port derived activity, were the colonial politicians & their treasurers’ primary impetus. In contrast, the priority in practically & collectively arranging for the defence of terrestrial Australia from foreign invaders was obviously an interest of lesser political weight.

Approaching Federation (which was proclaimed in 1901), the convention vote for Commonwealth (national government) control of the railways was only narrowly lost. This was despite the entrenched positions of the existing colonies. Moreover, there were several other curious aspects in respect of Australia’s Federation negotiations. First among them was that the Victorian leadership, and their citizenry, were at the time the strongest proponents of Federation, while the majority of the NSW elite were the most resistant. The NSW populace, in contrast, were shown to be supportive of Federation in the two referenda in the decade preceding the Proclamation.

What is confounding about the above is that the state of Victoria, otherwise in its history, has been regarded as the most protectionist of the Australian States; with NSW widely regarded as the most open & inclined toward trading externally. Further, the financial and fiscal responsibility shown by NSW was far stronger during the aforementioned period, as was demonstrated when Victoria had over-indulged itself fiscally (on asset price bubble spin off) during the goldfields boom, and then paid the price in the 1890s bust. My great-grandparents had indeed physically separated themselves from this bust by means of emigration to NSW.

Even more confounding, was that during the Constitutional bargaining, the delegates finally agreed to the supposedly legally commanding wording of Section 92 of the Australian Commonwealth’s Constitution:

“... trade, commerce, and intercourse among the States, whether by means of internal carriage or ocean navigation, shall be absolutely free.”

But if you thought this surely had established some productive high road in the Commonwealth, one that would, in and of the wording, regulation, and judicial decisions to follow, you would be quite wrong. You would indeed be omitting a century of state and federal licensing, monopoly/duopoly protectionist evidence of the same type that our friend Mr Gordon Barton willfully confronted as a young man.

Indeed, perhaps too Gordon took inspiration from his Sydneysider namesake Edmond Barton, Australia’s first Prime Minister, and a founding High Court judge. Edmond, despite his position among the NSW elite, was co-author of the “trade and intercourse ... shall be absolutely free" proposition at our first constitutional convention in 1891.

A small mercy to our readers is that we won’t labour through Australian High Court Constitutional case law in this blog series. It is sufficient to have observed that various licensing/regulatory regimes, & government mandated market monopolies/duopolies, had their place in restraining domestic ocean, air, rail, and trucking productivity nationally for over a century on our High Court’s watch.

In my own time, I can still personally reflect on several aspects that continued to debilitate the national transport market when I was a young man. I can recall in the mid 1980’s our trucking organisation having to secure interstate number plates in order for our linehaul fleet to be compliant with state and federal regulation when operating on interstate routes.

I also recall in the same years representing the Australian Federation of Air Freight Forwarders at the Aviation Law Association lectures in Sydney. There, a paper (presented by Peter McQueen) documented the constitutional legal questions in respect of a business operation of East West Airlines. This airline had sought to disrupt the then license backed airline duopoly accorded to Commonwealth government-owned airline TAA, and Ansett a privately owned competitor. The latter were licensed to exclusively carry air freight & passengers on interstate routes. East-West Airlines sought to fly freight from Sydney-to-Melbourne and return in competition. East-West then attempted to do so legally by undertaking a landing at the intermediate point at the state border city airport at Albury in order to utilise two intrastate licences to perform the task they were prohibited from performing on a direct flight basis.

Given the above as context, we will finally return today to an essential matter that we briefly raised in our first post. Protectionist State Government regulatory and capital expenditure biases in Australia created an essentially spineless domestic railway system. The rail network supported individual sea ports, and at each state border what may be called a defacto intermodal transfer was required (from one rail gauge to another). In the face of later competition from disruptive truckers, those that challenged state permit/licensing requirements, the government-owned intrastate rail freight networks degraded for lack of profitable business, and subsequently collapsed. In many cases, branch line operations (track and their rolling stock) reached such a low standard that they became unsustainable. Such is the state of much of the smaller retained branch line network bulk-carrying rolling stock that their employ also effectively requires de-facto intermodal transfers (to higher standard rolling stock) at junctions with mainline operations.

The reason that the rail network in the East Coast inland remains essentially spineless is derived of historical events, but these same political and monopolistic forces remain elemental influences in planning policies espoused today.

When we speak of a spine in rail, it is best to talk first of the contrary case, where Australian rail transport loads are primarily moved to-and-from ports. In most cases these ports coalesce with our major state metropolises and commercial distribution centres. When combined with the historical perspective, it may be easier to relate to my description of the rail network as it stands today as having, in the main, being framed as independent sets of tentacles emanating from the major sea ports.

In our next post we will seek to finally move on to a more contemporary footing. We will also start to look at recent Australian rail planning proposals and reviews. Moreover, as a counterpoint, we will start to discuss the shape of contemporary rail networks in the major developed regions of the world, those whose primary transportation infrastructure includes rail lines that not only serve as a spine, but also support a multiplicity of ribs. Moreover, the objective in pursuing of a spine and rib based rail network model is to seek to provide frequency, access, and economy for shippers and consignees in all parts of the network.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed