The structural changes to the movement of goods that come about in a particular era usually prove to have been necessary for commerce’s survival in those times. Outside of a return to a protectionist era, there is no choice but to improve our logistical efficiency. So the question is, will the infrastructure and the business regulatory environments keep up with essential needs?

Through to the mid 20th century, the primary form of long distance delivery of goods into Australian cities and towns for small businesses and consumers was achieved through the rail parcels office. In the inner city, the onward deliveries, or pick ups, from the rail parcels office were often made using trolleys.

Why is this important today? Because, in the e-commerce age, the idea of needing to make delivery by trolleys, due to voluminous & multiple party parcel delivery loads, is already becoming a reality. This is also being driven by the inability of drivers to operate efficiently while continuously needing to re-park within short distances in the emerging city and inner urban environments:

www.citylab.com/transportation/2017/04/cities-seek-deliverance-from-the-e-commerce-boom/523671/

Hence, the idea of mother-ships or parcels offices re-entering into the city and inner urban environs, those same that may offload to trolley operators, is likely not far from reality.

We have obviously digressed from our subject of inland rail, but we did so for a reason. We want to talk about market transitions and infrastructure corridors, and the above provides a foundation.

In the distant past, rail parcel offices in the city served much more contained delivery/pick up territories than is in evidence in inner cities today. Labour costs for messengers/delivery staff were also much lower then, so messengers moved over greater distances with individual deliveries. In those days too, there were also dedicated rail freight lines and better possibility for pathway sharing to feed the rail parcels offices than there is today. Hence, unless someone comes up with a form of modular feeder transport that can interact with the urban rail/metro system, yesterday’s infrastructure concept of a big parcels office near whatever central railway station will not serve us well.

The city-based logistical evolutionary process interests us. But the general subject we can employ to best effect in our case is found in local rail freight, and we will be using both Australian and overseas references in pursuing this theme.

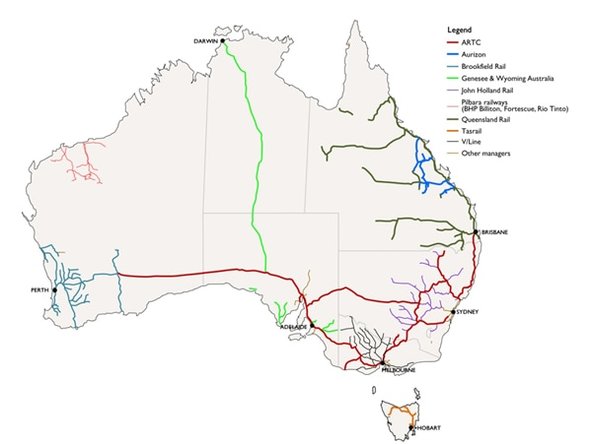

As discussed much earlier, Australia’s major coastal cities are also our port hubs. Where possible, however, the port terminals have been moved away from the city. In Sydney the dedicated rail freight pathways to those city port terminals were forsaken. In general, much heavy industry has moved out of the inner city, much production has been offshored, and some has moved to the periphery of the cities, yet only a little has moved to the inland regions.

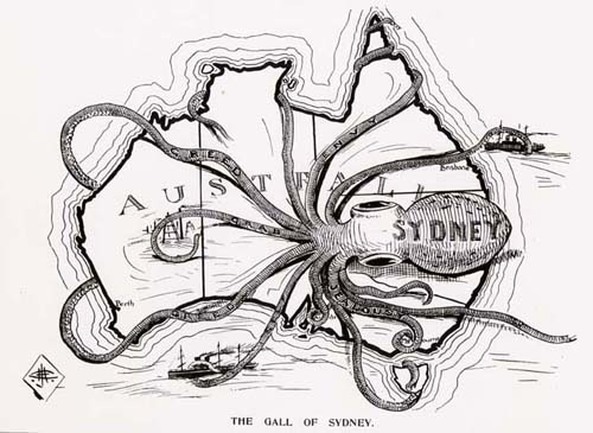

Your first thoughts may be of the great changes above, but if you look at it from the eyes of people and industries in Australia’s inland regions, not much has changed at all. The dominance of the freight moving into and out of the same port cities remains, because as the cities de-industrialised, an equal or greater flow of imports flowed into the city periphery distribution centres. The propensity of importers to employ a single national DC was also to mean that originating trends were not much different to manufacturers that had once sought to centralise production.

So there we have it, situation normal in Australia for rail connections, flow direction, and proportionate volumes running out of our metropolises mainly to other metropolises.

In respect of near-metro local rail flowing to the major metro rail yards, some of the dedicated rail freight lines that are being built to bypass the urban networks in our cities may have some potential to bring in some freight from additional production or DC sites at the city peripheries. However, the new dedicated lines are mainly conceived as bypasses and there is no strong growth prospect for local freight moving by rail across city-based railways in the metro environments around Australia as things stand. Real estate prices & urban planner’s designs upon industrial land mitigate against alternate prognoses. The major ports, however, are seeking to increase their use of intermodal terminals at the periphery of the cities they coexist with; if possible employing dedicated lines to reach these locations with shuttles. Hence, the major city-based rail yards are marshaling and creating train manifests in the same way they have for generations, but with long-since reduced local inbound rail feeding them wagons for classification.

Some of our Australian national rail infrastructure stakeholders, as evidenced in the 2015 report previously cited, have a fascination with things American. We can, however, state that in respect of local freight, things generally don’t play out the way we have described it above in the USA. The ports are relatively fewer, and they have larger hinterlands. Inland demographics and production are also far more evenly spread. Local rail freight usage, that which feeds rail yards, is strong across the country. Some of this traffic is borne in traditional carloads that are far reduced here. Moreover, carloads are intermingled with intermodal, tanks, and even bulk upon occasion. These same rail yards also tranship freight through their classification yards from inbound long haul services from domestic rail yards together with intermodal freight from ports. There is also the feed from regional intermodal terminals/rail ramps.

The US is a different operating environment when viewed from the Australian city-eyed perspective, but that same statement need not be so in the inland regions. We do not have the corridor congestion issues that might afflict local or regional freight feed in much of our inland regional environment. In fact, this problem is mainly confined to the narrow corridors and congestion approaching the ports/cities.

In many ways, given the proposed north-south inland corridor, we will have far fewer impacting issues than those afflicting the Los Angeles-Chicago intermodal express services cited in the 2015 Melbourne-Brisbane Inland Rail report transit time as a benchmark. For instance, the Americans have known for decades that they have severe corridor separation / bypass issues in Chicago, yet they have not been able to marshal the resources for the project to fix it. We have at least in part addressed such issues in Sydney and Melbourne.

We have again come along way today to make a very simple point in respect of the inland rail operating environment. While generating substantial rail freight volumes by employing local rail freight may not be achievable through a city/port based classification yard in this country, it is not necessarily the case in the inland regions. Moreover, the ability, at a limited number of strategic locations, to tranship tank, intermodal, and bulk freight through new or vastly improved rail classification yards on the proposed north-south inland rail corridor is probably both feasible and potentially game changing for Australian inland industry's prospects.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed